TORONTO - The binational organization tasked with recommending how Canada and the United States should protect the Great Lakes is expressing "disappointment and frustration'' that an agreement that hasn't been updated in 20 years appears mired in bureaucracy.

The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement was first signed in 1972, and at the time, then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau said it recognized "the fragility of our planet and the delicacy of the biosphere on which all life is dependent.''

"It promises to restore to a wholesome condition an immense area which, through greed and indifference, has been permitted to deteriorate disgracefully,'' he said.

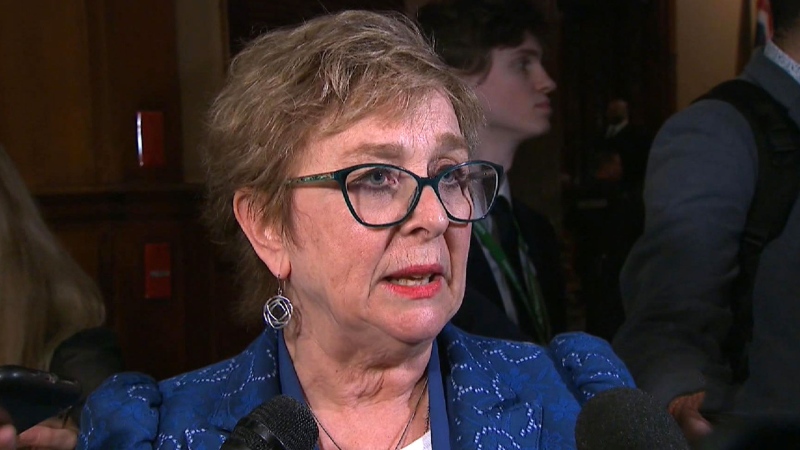

But not only has the restoration not yet happened, the condition of the lakes is worsening, and the federal governments of Canada and the United States are not reacting with the urgency required to save the "binational treasure,'' said Herb Gray, a former deputy prime minister and the Canadian chairman of the International Joint Commission.

The commission issued a report in December 2006 calling for "bold binational commitments'' and accelerated actions in implementing a new, "uncommonly strong'' agreement. The agreement hasn't been revised since 1987.

The Canadian government has since conducted its own review on the current condition of the Great Lakes but appears to be stalled in the next step, which is in tasking the Department of Foreign Affairs with opening negotiations with the United States to update the agreement.

The commission, which has been criticized in the past for being too diplomatic and not aggressive enough in pressuring governments, has sent a letter to the Canadian government calling for action, and a spokesman said the language being used is unusually strong for the commission.

"We're disappointed,'' Gray said in an interview with The Canadian Press.

"We've had a very good record over 100 years of our recommendations being acted on by governments, and we hope it'll be the case this time -- but we think things are going too slowly.''

A recently released report by the stakeholder group Great Lakes United suggests the agreement is in dire need of an update since its objectives are indefinite and outdated, and requirements are limited to simply reporting on problems rather than acting on them.

Co-author John Jackson said it's important that the process of updating the agreement -- which could take years to complete -- be launched as soon as possible with more public disclosure about exactly what's happening.

"The governments did their review and we haven't heard anything since,'' Jackson said.

"It sort of went into this dark hole and ... we've been given no indication of where the governments are at, which we think is critical.''

Jackson said he's concerned that the impending presidential election in the United States and the spectre of a federal election in Canada are delaying in the process.

But he called it an opportunity for Canada to take the initiative, since the United States has historically set the agenda in negotiations on Great Lakes matters.

"They come in and say, `This is our position,' and we say, `Well OK, we'll go along with that,''' Jackson said.

"We aren't the leaders, but now it's a chance for us to get ahead so when they're ready, we're really the leader.''

Gray said there's no excuse not to show more urgency in updating the agreement, considering the number of issues that have developed since the last update, and the wealth of benefits the countries share through the Great Lakes, which make up almost 20 per cent of the world's fresh water.

"We're dealing with a binational treasure that provides drinking water and sewage treatment for 40 million people,'' Gray said.

"It provides hydro power, water for navigation, it provides water for commercial and sport fishing, it provides water for industry and agriculture.

"There's so much there. It's not only environmental, it's economic as well. The two are not separate.''